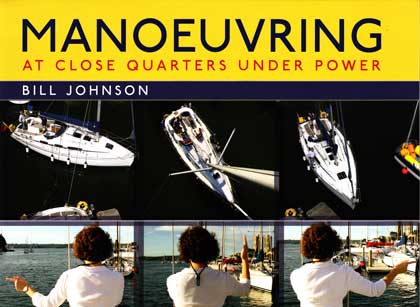

Yacht Manoeuvring at close quarters, using the engine

Yacht manoeuvring can make inexperienced skippers quite nervous, which is very understandable. You are in charge of a large, expensive boat, close by other large expensive boats and their owners, looking on critically – and this is a test of your new skills.

And it's not totally straightforward either. The yacht has an engine and a 'steering wheel', sure, but it certainly doesn't behave like a car (where's the brake?!) and it can be strongly influenced by wind and tide.

Not only that, this is probably the very first thing you have to do on the sailing charter: get the yacht safely out of the marina!

This book will help you. Manoeuvring becomes a great deal more straightforward when you understand:

• how the yacht behaves: how it speeds up, slows down and turns

• the means you have to control it, i.e. the engine control and helm (wheel or tiller), and how they work going forwards and astern

• the effect of wind and crucially, tide: on the yacht and on the manoeuvre.

You can look at the situation and plan your manoeuvre, knowing what will work and what strategies are available.

The book will also help you by recommending the best strategies in different situations.

Book Overview

The first chapter explains how the yacht behaves, and why.

It covers different yacht designs, and describes the use of the controls: the engine control and the helm. It explains the differences when the yacht is moving forward and astern, explains 'prop walk' and describes how you do a 'power turn' in a confined space.

It also explains how wind and tide affect the yacht, and how to modify your manoeuvring strategies in different wind/tide situations.

Sample pages are below.

Subsequent chapters look at particular types of manoeuvre in varying conditions of wind and tide. The manoeuvres covered are:

• mooring to a Buoy

• alongside a Pontoon (includes Rafting)

• marinas with Finger Pontoons

• fore-and-aft Mooring and Berthing (this includes pile moorings, trots, and fore-and-aft pontoon mooring, common in the meditteranean)

• harbours

• anchoring

• motoring at Sea (man overboard and heavy weather)

See sample pages below.

In each case the book covers arriving and departing, and there are clear diagrams showing the recommended approach for different combinations of wind and tide. There useful tips on most of the manoeuvres, to increase the chance of success.

The margins are colour coded so you can find easily the section you need. I’m not actually recommending that you use the book during the manoeuvre, but I suppose if you do need it – quickly – the colour coding and spiral binding might help significantly.

The main purpose of the book is to help you gain skill and confidence. So the best idea, when planning the manoeuvre, is to think of what might work and then look at the relevant diagram to see the approach it suggests. With your knowledge of how the yacht behaves, you should be able to work out why a particular approach is recommended.

To judge by the reviews on Amazon, readers (particularly relatively inexperienced skippers) have found the book very helpful.

To buy this book

You can buy this book from Adlard Coles Nautical (part of Bloomsbury), or from Amazon, or from any good bookshop or chandlery (complain if they don't have it!)

'Five Golden Rules' for Manoeuvring

Shortly after the book was published, I was asked to write an article on '5 Golden Rules for Manoeuvring'. You can follow this link to see it: www.ybw.com/specials/529933/five-golden-rules-for-manoeuvring. I've reproduced the 'Five Golden Rules' (not my idea, by the way - it's what the magazine wanted) below. It's all good advice, but definitely not the whole story - for that, you have to buy the book...

1 Use the tide

Always arrive at, and depart from, the berth or mooring against the flow of the tide – if there is any tide at all.

If you go in the same direction as the tidal flow, while the yacht is moving forward it may nevertheless be stationary in the water – so completely unable to steer with the rudder. This is likely to make manoeuvring tricky.

If you go against the flow of the tide – and this may mean going astern, particularly when leaving a visitors’ pontoon – you will be in complete control with the helm all the time.

You can also use the tide to your advantage: you can approach the berth or mooring as slowly as you like, or ‘ferry glide’ across the tide to get into (or out of) a tight berth sideways.

2 Go slowly

As a general rule, the slower you go the better – it gives you more time to think, and causes far less damage if it goes wrong.

The good news is that 90% of the time you can go as slowly as you like, and keep the yacht under full control.

There are some situations when you need use a bit more speed during a manoeuvre, and these generally involve the wind. A touch more speed through the water will give you more steerage so you can stop the bows from being blown sideways. Leaving a finger berth in a strong cross wind? Provided there aren’t any obstructions behind you, get the yacht out quickly, like a cork out of a bottle.

3 Take it calmly, don’t panic, and don’t try to show off

I know this is completely against some skippers’ natures, but it goes with the ‘take it slowly’ rule. It is particularly important if you ever want your crew to sail with you again. If they’re your family, for instance.

We’ve probably all seen examples yachts in marinas, roaring their engines as they accelerate forward, forced to use equal power to stop the yacht in its tracks before it collides with something else. The crew are rushing around with fenders in their hands and worried looks on their faces.

The panic, by the way, is signified by the skipper’s shouting. However imperious it sounds, it is a sure sign of naked fear.

And the showing off? Try flying a spinnaker up a crowded Hamble river and dropping it at the first bend. Then when the halyard jams and everyone rushes forward to sort it out, the guy at the helm starts the engine without noticing the sheets and guys trailing in the water … I've witnessed exactly that scenario (we towed them into the marina).

4 Not everything is possible

People get in trouble by thinking they ‘ought’ to be able to achieve a particular manoeuvre, rather than trusting their own judgement if they think it’s too difficult.

The very first manoeuvre on my Instructor exam was, naturally, leaving the marina. The unfortunate candidate who was picked to do it made the obvious assumption: ‘Surely this must be possible if the Examiner has asked me to do it?’ But the wind and the yacht’s prop walk made the ‘obvious’ manoeuvre practically impossible.

After the initial cock-up, the examiner suggested trying out different approaches to make the manoeuvre work, and we spent the next hour or so doing this. (The first guy passed, by the way.)

If you come back from a charter, and are faced with a blustery wind and strong ebb tide into your down-stream facing berth, then consider the option of parking on the hammer-head, walking up to the charter office and inviting them to have a go. They’ll probably leave it there till the next morning.

5 Try to do what the yacht ‘wants’ to do

Yachts are like people: it is much easier to get them to do what they want to do in the first place.

Very often there will be an easy way and a hard way to turn a yacht. The bows will tend to turn away from the wind, and prop walk will help in one direction and not in the other.

Look at both options, and try to go with what the yacht ‘wants’ to do.

The corollary of this rule is ‘If the yacht is already doing what you want it to do, don’t interfere.’ If you are turning the way you want to, to get out of a tight spot, or drifting slowly away from a mooring buoy after slipping, simply wait. Don’t rush into gear and run over the mooring.

And finally …

The real key to manoeuvring a yacht under power is understanding what’s going on, and being able to anticipate how the yacht is going to behave. That’s why ‘Manoeuvring’ starts with a comprehensive chapter about ‘How a Yacht Behaves and Why’, before going into what you do in different circumstances.

So good luck, good yachting – and buy the book!